It has long been observed by residents and visitors alike that each and every island has its own feel and character. This is also true of their flora and fauna, even though they may be connected by causeways or separated by just a few miles of open water.

As residents of these islands, we are frequently asked about the status of birds on the individual islands. What may be a common sight on one island is a rare occurrence on another. A report of a Shoveler would not raise an eyebrow on South Uist but be greeted with excitement on Barra or Vatersay. Such are the anomalies here in the Outer Hebrides.

I am therefore hoping that this guide may go some way towards answering that question by updating the current status and distribution of birds on the individual islands and outliers.

Geodha Martainn, Harris © Hebridean Imaging

It is hoped that by producing this guide as an online resource, it can be more readily updated and evolve as our knowledge increases. It has been compiled primarily from past literature, the county archives, past bird reports both national and local, rarities committee reports and BirdTrack, plus a wealth of additional information provided by Andrew Stevenson.

When considering the records available for review, a decision was made to include all the birds that have occurred in the Outer Hebrides but to document their status and distribution from 1990, when the first Outer Hebrides Bird Report was published. For the scarce and rare birds, the historical records and reports have been included where known and most dates quoted are after 1958, the year the British Birds Records Committee published its first annual report. Records prior to that date have been included if there was a sufficient level of confidence in their authenticity.

This guide primarily covers the Long Island which is Barra to the Butt. Although the Outliers are an intrinsic and important part of the Outer Hebrides, in recent years there have only been sporadic reports and information coming from St. Kilda, the Shiants and Mingulay. I reluctantly had to concede that there was insufficient data to assess the status of birds on these smaller islands and they have therefore not been considered for many species. The one exception is St. Kilda where records are available up to 2000 but many refer to the number of occurrences without any reference to dates. Thereafter, information was received only when a more communicative warden was in residence. However, many of these records have been included in the species accounts but most relate to the more scarce or rarer species. For all the other Outliers, where records have been made available, they have been included but again they mostly concern rarities or information regarding historical breeding colonies. This will hopefully be revisited at a later date.

This guide will undoubtedly contain mistakes, omissions, and errors, but hopefully much will be rectified over the passage of time. Many will be down to the editor, but there are a great many undocumented records and this, combined with the difficulty in being able to cross reference records in past literature and the archives, will inevitably lead to inaccuracies. Should anyone have any additional information or records, spot any errors or omissions, please do not hesitate to contact us.

There are also some “thin” species accounts where our knowledge is sadly lacking. There are many reasons why this has occurred but primarily it is due to the fact that there are very few or no recent records for these species. Most of the records received are from the Long Island, primarily the Uists and Barra with far fewer from Lewis and Harris with the exception of a few hot spots, and then they most often refer to the less common or rarer species. Because the more common species tend to be under recorded, especially on Lewis and Harris, some of the species accounts for those islands are sadly lacking in detail and may well have changed in recent years. My hope is that this guide may stimulate visiting and local birders alike to submit more records. I am also sure that there is a wealth of information out there somewhere but probably remains buried in personal notebooks or spreadsheets.

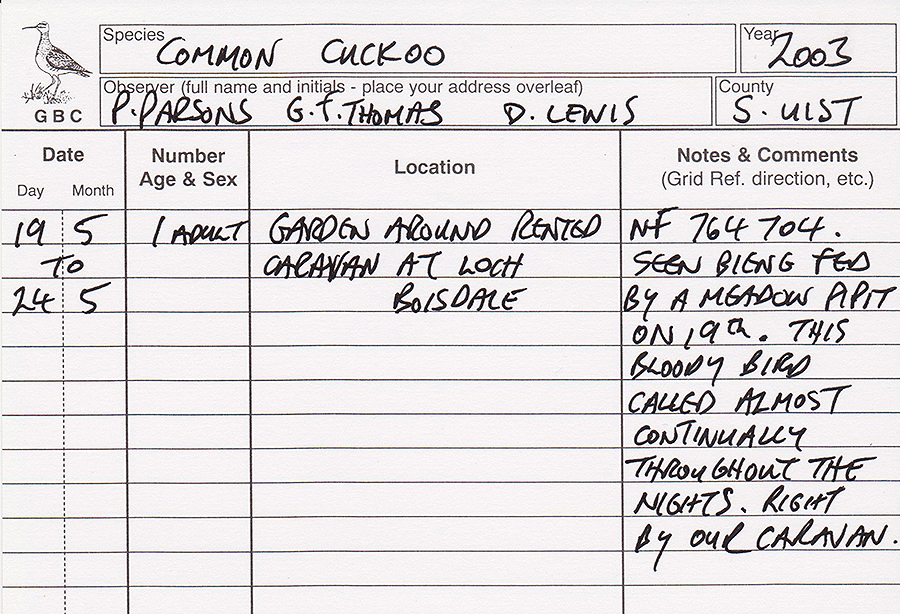

A 2003 records card, how records were once received

The low level of recording on Lewis and Harris is not a new phenomenon as noted by Peter Cunningham’s Nature News article in the Stornoway Gazette when advertising the 1998 bird report. He, even then, lamented the level of recording on Lewis and Harris by writing (as a resident of Lewis):

“Readers in Lewis and Harris may be a little scunnered at the disproportionate number of records from the Southern Isles, but it is our own fault. The Editor can only publish what he receives, and it beholds us to try to give him more news for next year’s report.

Unfortunately, this situation still exists today and may have even become more acute.

Local rarities too are now often not documented which means that those records are excluded, and valuable data is lost. This is an unwelcome trend which is now happening with greater frequency for Scottish, and, to a lesser extent, national rarities too.

With the above in mind, I would just like to reiterate to local and visiting birders alike, your records are valuable, so please make sure that they are received by the county recorder. They only way to do that with any certainty is directly, either through BirdTrack, by posting on or communicating via the Outer Hebrides Birds website, or by emailing the county recorder. If you publicise your records solely by other means, the recorder may not find out about them.

This guide is only as good as the records which have been provided.

As for the environment, much has changed since Peter Cunningham’s first edition, the most noticeable being the influence that woodland is now having on our birds. The increasing extent of maturing woodland in such areas as Stornoway Castle Grounds, Langass Woods and North Locheynort, in domestic gardens throughout the islands plus widespread maturing conifer plantations, appear to have had an impact on some species numbers and their geographical distribution. Aline Forest, Lewis, is but one example. Comparable in size to Stornoway Castle Grounds and although a dense and impenetrable coniferous monoculture in places which limits its value as suitable habitat, it nevertheless has attracted the commoner woodland species such as Blackbird, Robin, Wren, Willow Warbler, Coal Tit, Goldcrest, Goldfinch and Chaffinch, all of which have taken advantage of this habitat to increase their population numbers and geographical range.

Further changes are afoot with the possibility of much more open land being converted to woodlands with the Woodland Crofting scheme. The take up and planting of large areas is variable across each island but with areas of Barra now being planted, a fundamental change in woodland bird species is expected as the trees mature.

Not all species have been so fortunate. Once a common sight and sound throughout the Outer Hebrides, for whatever reason, the Corn Bunting has withdrawn in ever decreasing numbers to the Balranald / Paiblesgarry area of North Uist. Breeding waders and terns associated with the machair are also in a slow but steady decline as they are throughout the UK. The reasons are probably complex and varied but increased disturbance, predation by invasive non-native species such as hedgehogs, cats, rats and ferrets, plus possible changes in farming practices such as the use of chemical fertilisers instead of seaweed must all take their toll. Add climate change to the mix which is affecting our seabird colonies which have suffered dramatic breeding failures in recent years due to a lack of sand eels, and the future does not look bright for these species.

The bird communities of the Uists have long been shaped by Human activities and the 20th century may well have been a “golden age” for the birds of the Uist machair, even though human populations were larger and disturbance, exploitation of birds for food and intensity of land use were likely to have been higher. The past forty years have seen large changes in bird populations and further change seems likely. Future changes in agriculture practices such as a shift away from cattle towards sheep farming would result in the cessation of cultivation, the loss of plant-rich fallows and more uniform grassland.

It is only through your records that these and future changes can be documented.

Harvest time, South Uist © Hebridean Imaging